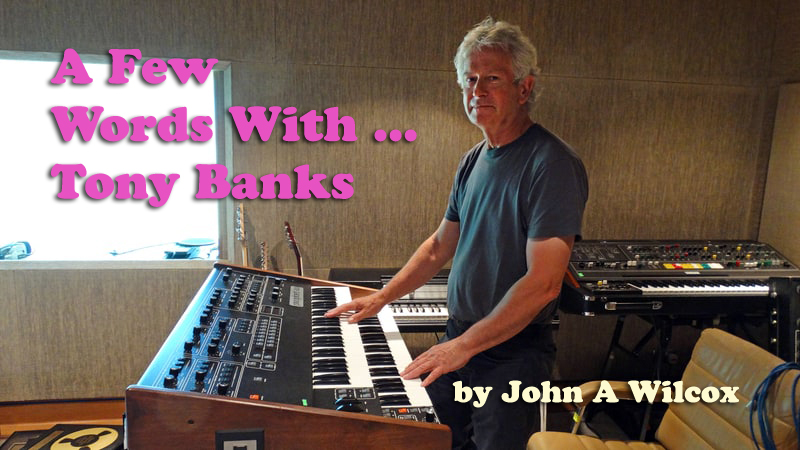

A Few Words With ... Tony Banks

by John A. Wilcox

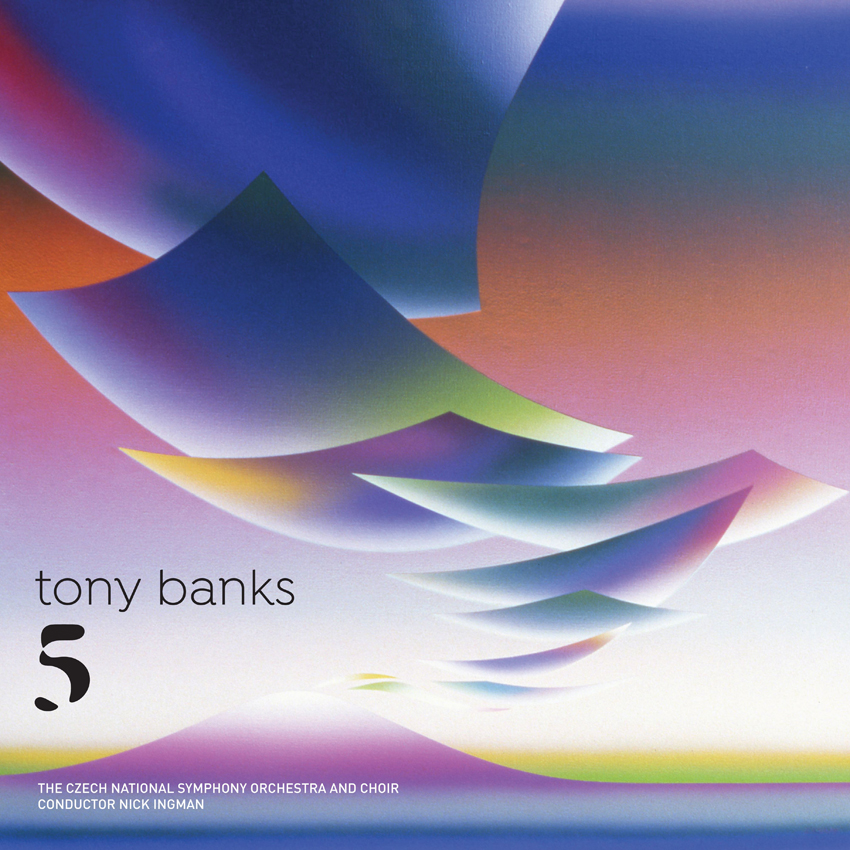

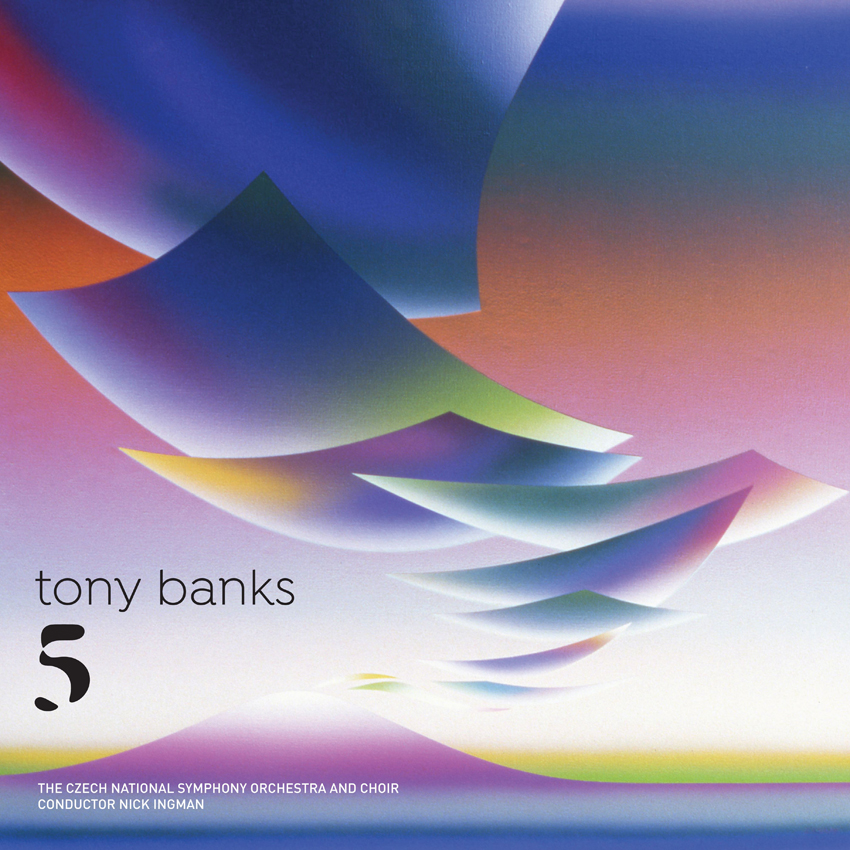

Five is the 3rd orchestral album by Genesis keyboardist Tony Banks. For this outing he is joined by conductor Nick Ingman and the Czech national symphony orchestra and choir. Banks and I dove into the construction of the album as our starting point. Read on...

PS: I understand that the opening track, Prelude To A Million Years was the first piece you worked on for Five.

TB: Yes, it was the starting point. I was originally asked to write a piece of music for a music festival here, a place called Cheltenham. It's quite a thing over here, it's quite a reasonably prestigious place. The piece I wrote was this prelude. At the time it had a working title of Arpeggio, which is what it was performed under at the time. Although we changed the arrangement a bit since then it is pretty much the same piece of music. It was the starting point for this record.

PS: It struck me as being quite an expansive piece.

TB: It is an expansive piece. It's got the slightly pretentious title of Prelude To A Million Years, which is a sort of borrowed title. It's supposed to encompass a lot. It's a 15 minute piece and it goes a lot of places within lots of different tempos. Very slow at times and very fast at other times. Hopefully giving a unified story, which is the idea.

PS: What was your mindset after being asked to come up with a piece for the festival?

TB: Well, I asked them how long they wanted it to be and they said, "Well, about 15 minutes," and I thought, well, that's good because I'm sort of a long-winded person. I had a few ideas around and a couple of ideas I thought of developing and the particular one that I ended up developing was the one that became this prelude. I thought I'm not going to restrict myself, I'm just going to do what I feel like doing. I wrote a piece that was probably complicated to be used at the festival, because obviously you're only hearing it for the first time and it's got to work in one go. Some of the music goes too many places for a one-off performance. I'd always had in the back of my mind that if I wrote something, I'd probably be using it for something later on, so I didn't really worry too much. When they played it live some bits worked quite nicely. The slow bits sounded great but some of the faster bits weren't quite so good.

PS: Why did you choose to bring the Czech national symphony orchestra on board for the album?

TB: I'd worked with a Czech orchestra on the previous record I did and I kind of liked that situation. When we did the thing in Cheltenham it was with an English performance symphony orchestra and although they're fine, the attitude of English musicians is slightly different, so I intended to go abroad and make it. I wanted to get a slightly different kind of sound. The way I did this record was slightly different to how most orchestral things are done.

I used my original demos, which I worked quite hard on, as a kind of template and put all the orchestral parts to that template, replacing what I had done with the samples, if you like, as I went along. We embellished and added lots of stuff as well, What I wanted to do with this was to control, more than anything else, the tempo. I found on my previous pieces sometimes the tempo got away from me a little bit. Classical music, not being done to strict tempo, a lot of moments that are quite different speeds from other bits. I've never been totally happy with what had happened in the past, so this time I thought I'd get all that completely sorted. It's much closer, or very close, to what I originally had in my head. For that reason it was fun to do that way.

PS: That reminds me of how Brian Wilson handled the recording of Pet Sounds - recording all the vocal parts himself, then bringing in the others to sing over his parts.

TB: It's fair to say that a lot of rock music is done kind of like this. When we worked with Genesis we'd often put down a fairly skeletal part. We'd load up the drum machine and then we'd play along with that. We'd add to it and embellish often, just doing it with "na na" type vocal. You have all the essence of what you want, it's up to you to dress it in such a way that it comes across to an audience, and that's sort of what I was trying to do with this. Pet Sounds was one of the earlier albums to do this kind of thing, and it came from one head, whereas when you're working with a group obviously everyone's involved. This is a similar approach - a lot of rock music is done this way where it's kind of built up over a period of time. Not everybody plays on the same time in the way that orchestral albums would normally be done in the past.

PS: What lessons did you learn from your 1st 2 orchestral albums that you were able to apply to this one?

TB: The first one I learned quite a lot because it was the first time I'd ever done it. It seemed to me that the slower pieces were much easier to do. The first thing I wanted to get was an orchestra who can understand rhythm in the same way that you do, which is interesting because classical musicians do have a different approach. There were parts on the very first one of these I did, particularly the final piece - The Spirit Of Gravity - where it took quite a lot to get the orchestra to play rhythmically how I intended it. To be honest, given the time we had and everything, I never got it quite right. I was rather disappointed in that piece. It made me realize that next time that I wanted to make sure that I had more time to rehearse.

When I did the second one we did it much the same way in a sense, recording everybody at the same time. I had much more rehearsal time with the orchestra so we got it all right. As soon as we went into the studio to record the piece, at least they knew what they were trying to do. We got rid of all the errors on the scores as well. When I finished that one, again, two or three of the pieces turned out great, two or three of the pieces didn't work so well. The problem was it had gone further away from my original conceptions than I wanted it to, particularly with the timing. The tempo was a big factor. Also, sometimes the arrangements didn't do exactly what I thought they were going to do. On this one I wanted to try and get as much of the arrangements totally fixed before we went in. I did a lot of it myself and then I had some help from Nick Ingman who is also the conductor on this piece. He got very inside the music and was very helpful. He basically transcribed all the things I'd written, embellished, and then added to them as well. We were in contact all the time saying this works, this doesn't. When we went in the studio and started recording, we had a pretty clear idea of what we wanted to end up with, so the pieces ended up sounding pretty close to what I had originally got in my head.

PS: Reveille features cross-hand piano technique that you used on several occasions dating back to the seventies.

TB: As you said, I have this sort of cross-handy thing which I used a lot over the years. I don't really see this as a Genesis-y, I just had this little riff going and I always like the little things you get when you do the cross-hand thing. What's quite fun is that sometimes when you put your fingers down, you don't know quite what it's going to sound like because you play things in different orders and you get things you didn't know about when you were writing it. That's quite fun. Actually, I had a fairly reasonable sort of part going. I knew it needed some kind of top line. So I first started improvising using a trumpet, so the idea of playing this melody then worked with that sort of sound came about. It's very fast and very tense. At some point I thought, "I can't keep this up forever, I've got to go somewhere else." So I slow it down and go to a related theme that is much more mellow and slower. It gave me the opportunity to then go back to the fast stuff again which is also quite fun because of a bit of a key change, and to suddenly gear up makes it sound exciting again.

I see this as perhaps the most "instant" of the pieces on this, I don't see it as particularly Genesis-y. I think in many ways some of the other pieces are more Genesis-y in a way. I mean, I'm obviously part of the writing of Genesis and particularly influential in those early days when we were doing slightly more extensive pieces, so it's not surprising that there are references - everybody sounds like they sound. However much you try and sound different, you often end up sounding similar, even the greats. The relationship between Beethoven's first symphony and his ninth, I think everyone has a certain approach to music and it tends to come through. Not many people manage to be completely different at different times.

PS: How did Autumn Sonata come together?

TB: I started off trying to write a melody that just was on 2 chords. I had the first line when I thought "That works nicely." I'm always a person to always add another chord here and there when I shouldn't. I almost managed to do the melody once through only using 2 chords. Adding a third chord right at the end because it had to be there. And then, of course, I let myself go after that and I played the same melody with much richer chords and everything. But I think it still kept that simplicity. It's kind of written in a more conventional form. It's almost sonata form. That was something I'd written quite recently. I had another bit I'd written 2 or 3 years before and hadn't yet found a home. I wanted this piece to go somewhere else. So that's when I went into the middle part which features the trumpet section and then there's a very long build-up which involves marimbas and celestes and everything. Quite simple piece.

Another thing I wanted to try and do was use a very simple almost rock 'n' roll chord sequence like Bread And Butter by the Newbeats (sings lick). Just doing that with the marimbas and piano, and then developing that into a piece. Just getting bigger and bigger and bigger til you get to this very big rundown where the trumpets are all going and the choir comes in at that point. Like all these pieces, you try to take it to a certain place and then you get to a big climax and then you come back again to the original melody, a little more embellished and it sounds very friendly by comparison to what's just come before it, and then it goes back again. I write in a way that my mind lets me go. I like transitions. It's one of the things I'm very keen on in music. Between soft and loud bits, simple and complex bits, and hard and soft bits, I think that makes each bit sound more distinctive in itself.

PS: Does expectation ever play a factor in a project?

TB: It doesn't really. Many people say this isn't the album they want to hear from me. They might want to hear an album that's much more heavily keyboard-based and perhaps with drums and stuff. I just got into doing this because, as I'm sure I told you many times before, in the late '90s when Genesis had done the slightly unsuccessful tour with Ray Wilson as the singer, which I thoroughly enjoyed the music to that actually, a lot didn't. It looked like Genesis was probably going to fold in one way or another. I thought, "Maybe that's it." I was nearly 50 "Maybe it's time to stop and do something else." I thought I'd always wanted to do an orchestral record or orchestral music since I'd done the film music for the film The Wicked Lady many years before. Although not a very good film I thought that the music worked very well. I thought "Before I finally give it up, let's give it a go!"

So I did the first one of these - Seven - which proved to be the most successful of my solo albums, really. So it gave me a new lease on life, if you like.The previous one, Strictly Inc., which I thought was probably one of my best albums of all, had completely gone without a trace.When I did Seven it was a new lease of life and given me the opportunity to do these two - Six and Five - afterwards. I'm sort of getting better at it. More confident. I love writing music. The part I enjoy least of all is putting the things out! Then you've got to worry about other people's opinion. But when I'm making the things I really don't think about anybody else. I just do something I like. Over the years with Genesis that worked very well. Things that I liked fortunately an audience liked as well. The only problem you have a little bit when I do anything on my own is just to get noticed I suppose. Which is a problem everybody has. To make certain that people hear the thing so they can judge for themselves whether they like it or not.

PS: There are so many albums being released nowadays it's like being a BB in an aircraft hangar.

TB: It's very difficult to get noticed. Because I have the Genesis connection it means I have some people follow what I do. It tends to be that I get an initial number of people who go out and try and get ahold of the thing, if you like. But to get beyond that is very difficult. I think that for anybody who's coming from nowhere it's even more difficult. You need a bit of luck. Some people manage to do it through things on the internet. Sometimes it just captures a mood somewhere. These days mainstream pop music is very simple. Going through a very simple phase again. Keep the chords simple. Keep the melody line very simple. Which is, of course, completely alien to me. I kind of like going the other way I suppose. Still, obviously, there is prog music out there and stuff like that, but it has a much lower profile than when we were doing it.

PS: Sometimes I worry that too much of what we currently call prog is stuck in 1974.

TB: That's probably true to some extent. That's the only problem with calling it prog. The whole nature of prog music when it first came out was that it was completely different to anything that had happened before. It was trying to take some of the elements of more complex music and doing it within a rock context in many ways obviously expansive in terms of lyrics. If you do it again now, you are just repeating, in a way. It needs to go somewhere else, but quite how or where I don't really know. I just think there's still people out there who like to hear music that is a bit more involved. If that means recalling the early seventies music, then I suppose that's one way of doing it. That's why people do it.

PS: There was a time when if you wanted to hear Genesis music played live, you had to go see...Genesis. Now there are an untold number of bands performing every era of Genesis music. What are your thoughts on that?

TB: It's very flattering to still have the stuff played. The groups like Musical Box tend to do it very much in the style we did it. They often copy our arrangements completely. It works fine. They play better than we played back in the early days. I like when people do other arrangements of our pieces in a way. Of any period. I haven't heard much of what Steve's done but everybody tells me much of his versions are slightly different to what we did, which is good as well, I think. There's been a cover version of Land Of Confusion which was definitely different which was really nice too. I like hearing people trying to do something slightly different with the music as well as doing it the other way.

When we were doing the stuff, particularly the music up to 1974, it wasn't universally...liked, if you know what I mean (laughs). It was quite difficult at times to get the audience to respond to it. We had a very strong following but they were small. Now it seems to me that these groups that cover other groups can play places bigger than we played it first time out. It is interesting, isn't it? It's now 50 years since our first single was put out - The Silent Sun - back in 1968. It's just so amazing. When we put that out the concept that anyone still would be interested in our music at this stage even in our wildest dreams we wouldn't have thought that was the case. Particularly after we put the record out and it didn't do anything. I think we were lucky that the kind of thing we wanted to do would actually be right for the time. People were looking for a slightly more elaborate kind of music. It had been shown where you could go in the mid sixties with people like the Beach Boys and the Beatles. Then groups like Pink Floyd started to take it somewhere else. We were able to get into that and go somewhere quite a long way down a road that was not apparent could be gone down when you think of the kind of music that was around in 1961. It changed a great deal.

###

Table Of Contents

Contact